Blog post by Ellie King, MSc Museum Studies Placement Student, William Hunter’s Library: A Transcription of the Early Catalogues. Ellie worked on the Hunter Library Project from May to July 2017 to help with background research and book history enquiries, and also assisted in work with sale catalogues to determine where Hunter acquired his books. She has curated in advance a small display based on her work which will be exhibited from January – April 2018 to mark the start of Hunter’s Tercentenary year.

William Hunter is famous for his medical work, but the catalogues of his book collection show the wide range of his interests. Today the spotlight is onAmericana— descriptions of the New World.

Travelogues and descriptions of exotic, faraway places comprise a significant part of Hunter’s library, and cover both the Old World and the New. His Americana books are rich accounts of voyages to the New World, and present exciting visions of America. Some realistically describe the new continent, while others present a fanciful vision of both savagery and abundance.

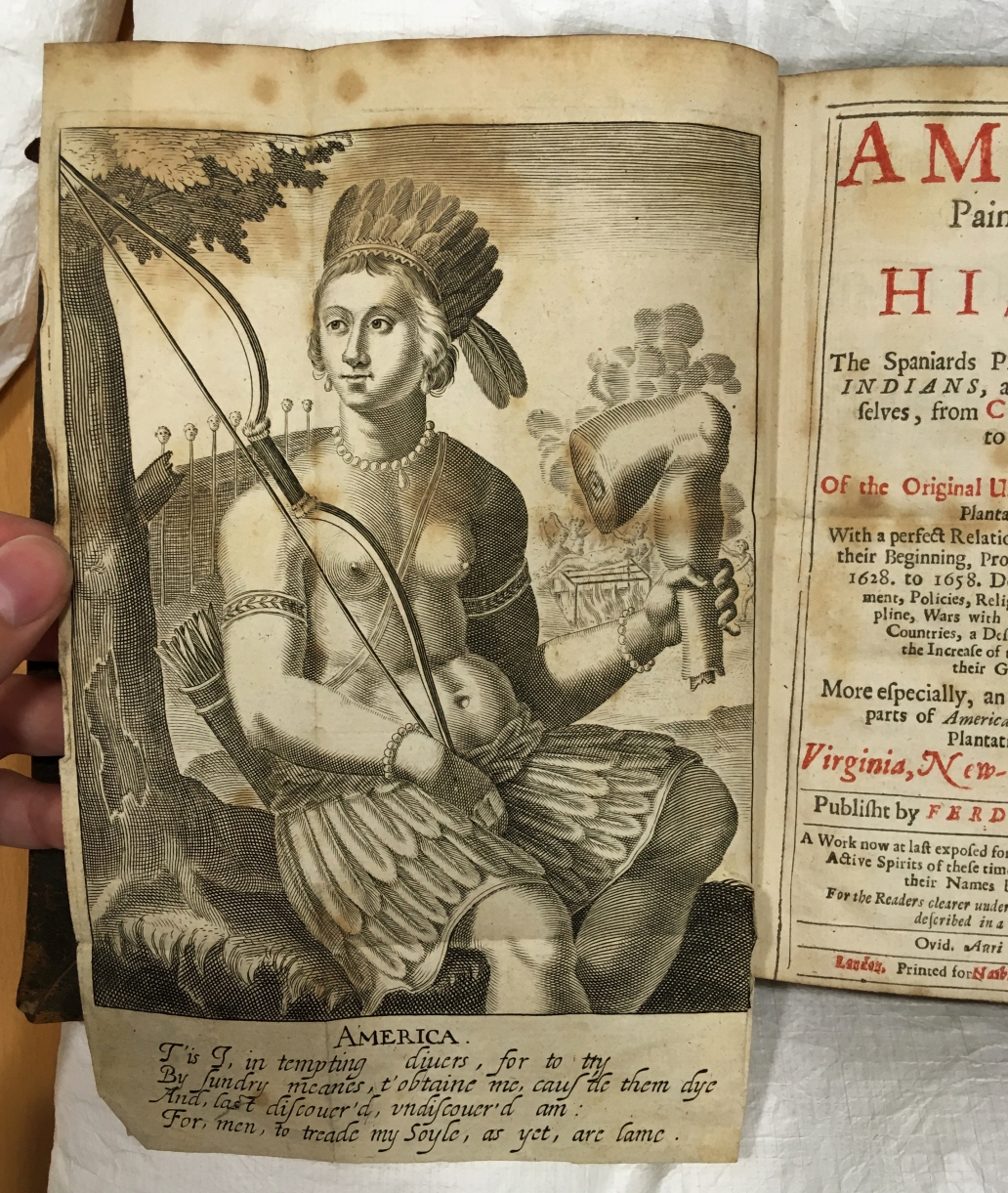

A gory allegorical image of America in human form, conveying the perceived savagery of the indigenous population. Published in Ferdinando Gorges’s 1659 work,America painted to the life

Two Hunterian Library projects are currently in progress in Special Collections. As well as creating a digital version of Hunter’s catalogues in a Wellcome funded project, a Leverhulme funded PhD student (Michelle Craig) is investigating the provenance of Hunter’s books, including how he acquired the titles now found in the early catalogues. It is evident that Hunter scoured London book sales and auctions and spent vast sums of money buying books from a wide range of people, from fellow doctors to politicians and clergymen. Some are well known, such as Joseph Letherland (1699–1764) who was physician to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. Others are more obscure.

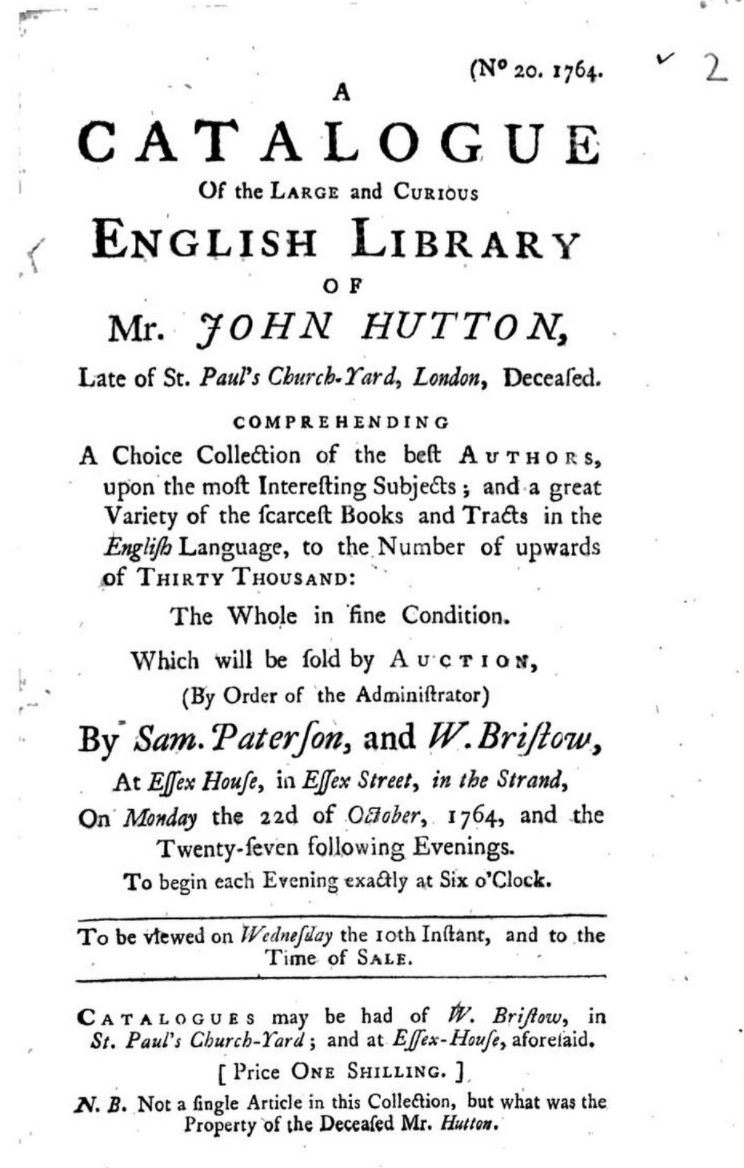

In 1764, Hunter bought a collection of Americana from aMr John Hutton, late of St Paul’s Churchyard. Mr Hutton is elusive: no clues to his identity seem to have survived. A trip to the National Archives and a search through 18th century wills are perhaps needed. Unfortunately, John Hutton is a relatively common name, and the matter is complicated by the existence of two better-known John Huttons from around the same time: a Scottish surgeon, and the botanist John Hutton Balfour.

Sales catalogue of John Hutton’s library, 1764. You can browse a digitised version of the catalogue viaGoogle Books

While John Hutton the man remains a mystery, an idea of his interests can be deduced from the books that Hunter bought at the sale. The 30,000 books offered in the Hutton sale were all in English. Although the use of the vernacular was growing through the Enlightenment, most scholarly books were still written in Latin or Greek.

Many of the books in Hutton’s collection were written in English by English-speaking authors. However, many were translations. Most descriptions of South America were written in Spanish, and consequently there was often a significant delay before these works were translated into other European languages.

One such work was Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma’sCurioso tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del chocolate(A curious treatise on the nature and quality of chocolate), published in Madrid in 1631. The Hutton sale provided Hunter with the 1652 English translation by James Wadsworth, titledChocolate, or an Indian Drinke。This was the first description of the medical uses of chocolate in Europe, using the Four Humours system which had predominated in European medicine since Hippocrates and Galen, and was almost 2000 years old by Colmenero’s time. The book presents chocolate as the 17th century superfood, curing everything from ‘plague of the guts’ to tooth decay!

Readers would also have found Europe’s first recipe for hot chocolate, along with dire warnings of stomach aches and melancholy if drinkers did not follow Colmenero’s precise instructions. For your delectation, the recipe:

To every 100.Cacaos, you must put two cods of the long red

Pepper, of which I have spoken before, and are called in theIndian

Tongue,Chilparlagua; and in stead of those of theIndies, you may

take those ofSpainewhich are broadest, & least hot. One handfull of

Annis-seedOrejuelas, which are otherwise calledPinacaxlidos: and

two of the flowers, calledMechasuchil,如果腹部被绑定。但在

stead of this, inSpaine, we put in six Roses ofAlexandriabeat to

Powder: One Cod ofCampeche, or Logwood: Two Drams of Cinamon;

Almons, and Hasle-Nuts, of each one Dozen: Of white Sugar, halfe a

pound: ofAchioteenough to give it the colour. And if you cannot have

those things, which come from theIndies, you may make it with the rest.Colmenero“最好的收据”的热巧克力translated by James Wadsworth. You can read a full transcription of the text at theLambertville Free Public LibraryorProjectGutenberg

While Colmenero’s book fits neatly into Hunter’s medical collection, other items of Hutton’s Americana are broader in scope.

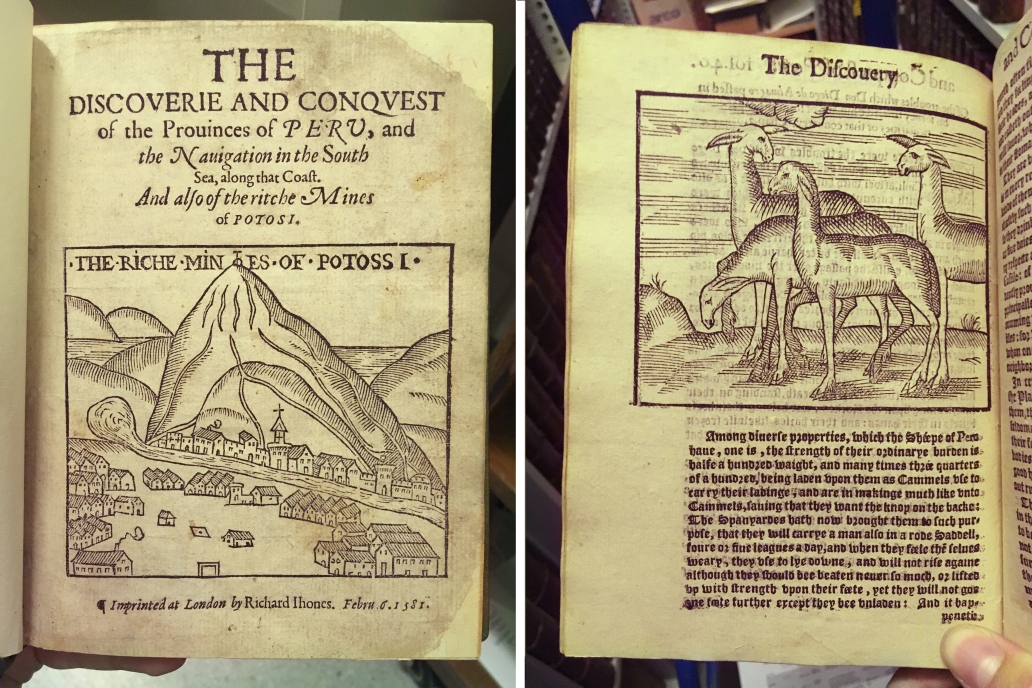

Agustín de Zárate’s 1555Historia del descubrimiento y conquista del Perúwas published in English asThe history of the discovery and conquest of the provinces of Peruin 1581. It is an account of the conquest and the subsequent in-fighting among Spanish conquistadors, written by an accountant who travelled to the New World in 1543 under orders to oversee the royal hacienda (royal estate). The book was published at the command of Prince Philip of Spain, who would later become Philip II and husband of Mary I of England. While supposedly a simple account of events, Zárate muses on the origin of the peoples of the New World, using passages of Plato to argue that Andean civilisations came from Atlantis.

The English translation of Zárate’s work also describes the flora and fauna of the New World, and includes the first image of llamas in an English language publication, calling them ‘the Sheepe of Peru’. Although llamas had been depicted and described in Pedro Cieza de León’s 1553Crónica del Perú(alsoin Hunter’s library, but not bought from Hutton), this was not translated into English until the 18th century.

Agustín de Zárate,The history of the discovery and conquest of the provinces of Peru(1581),Sp Coll Hunterian Cp.3.13

Although the Spaniards had ransacked the New World looking for gold, it was silver from the mines at Potosí in modern Bolivia that funded the Spanish Empire’s further expansion. These mines are described in Zárate’s text. Cerro Rico, or ‘Rich Hill’ was the world’s largest silver deposit, providing the Spanish with more than 40,000 tonnes of silver over 200 years, at huge human cost to the local indigenous population, who were forced to mine the silver in treacherous conditions. Some estimates suggest mining at Potosí has cost up to 8 million lives since the 16th century.

Llamas were used to carry loads of silver ore down the mountain. Potosí was the source of most of the silver used to make ‘pieces of eight’ — Spanish eightrealcoins. Pieces of eight became the first global currency, and were the basis for the original US dollar. They were legal tender in the US until 1857. In Hunter’s day, at the height of its power, the currency was in use from the Americas to the Far East, but in popular culture the coin will forever be associated with pirates, thanks to Robert Louis Stevenson’sTreasure Islandand Disney’sPirates of the Caribbean, as well as Sir Francis Drake’s capture of Spanish treasure ships in the 1570s.

Enter a Piece of eight minted at Potosí in 1734. From the collection of theBank of Canada Museum

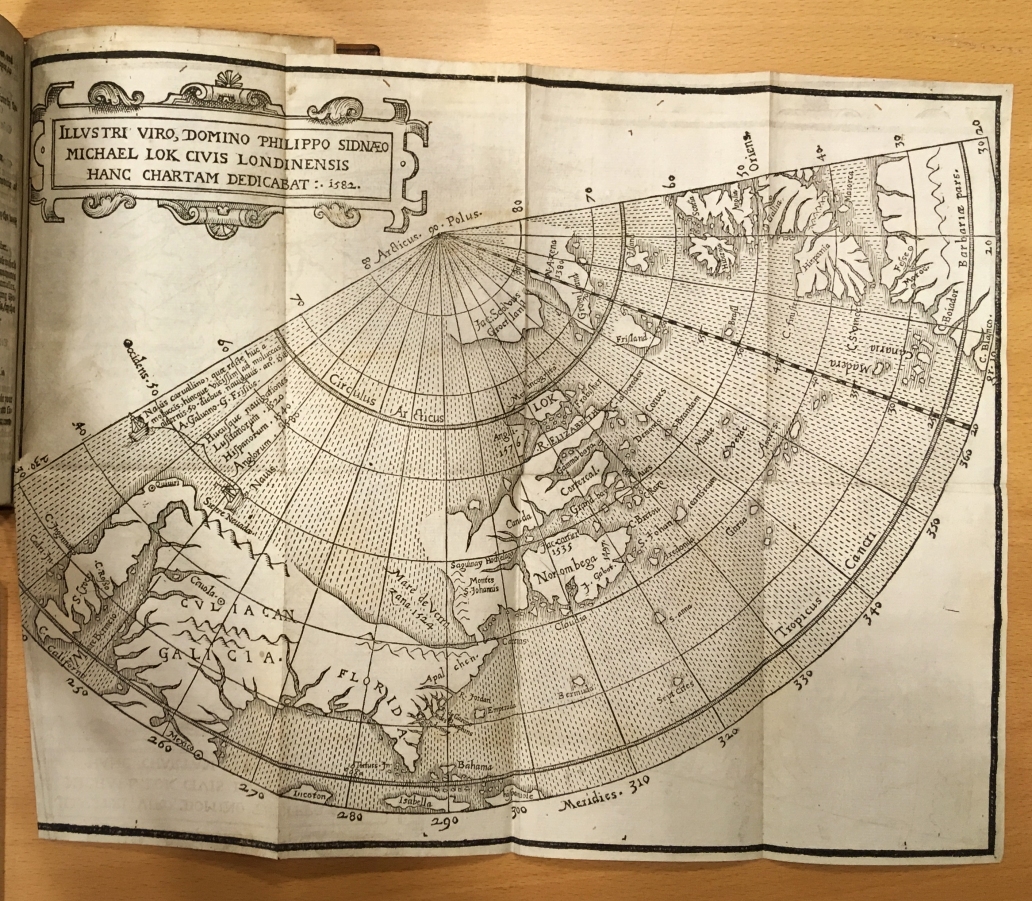

Zárate and Colmenero both travelled to the Americas themselves, but Hunter also acquired the accounts of armchair travellers. Looming large among these was Richard Hakluyt, an influential Elizabethan geographer. The explorer Sir Walter Raleigh, the spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham and the poet Sir Philip Sidney were early readers of Hakluyt’s work. At the Hutton sale, Hunter acquired Hakluyt’s first book, the 1582Divers voyages touching the discoverie of America。Hakluyt was more editor than author, and theDivers voyagesis a compilation of texts collected and in some cases translated by Hakluyt to argue for English colonisation of Virginia. He would build on this argument in later publications, culminating in his most famous workThe principal navigations, voiages, traffiques and discoveries of the English nationin 1600.

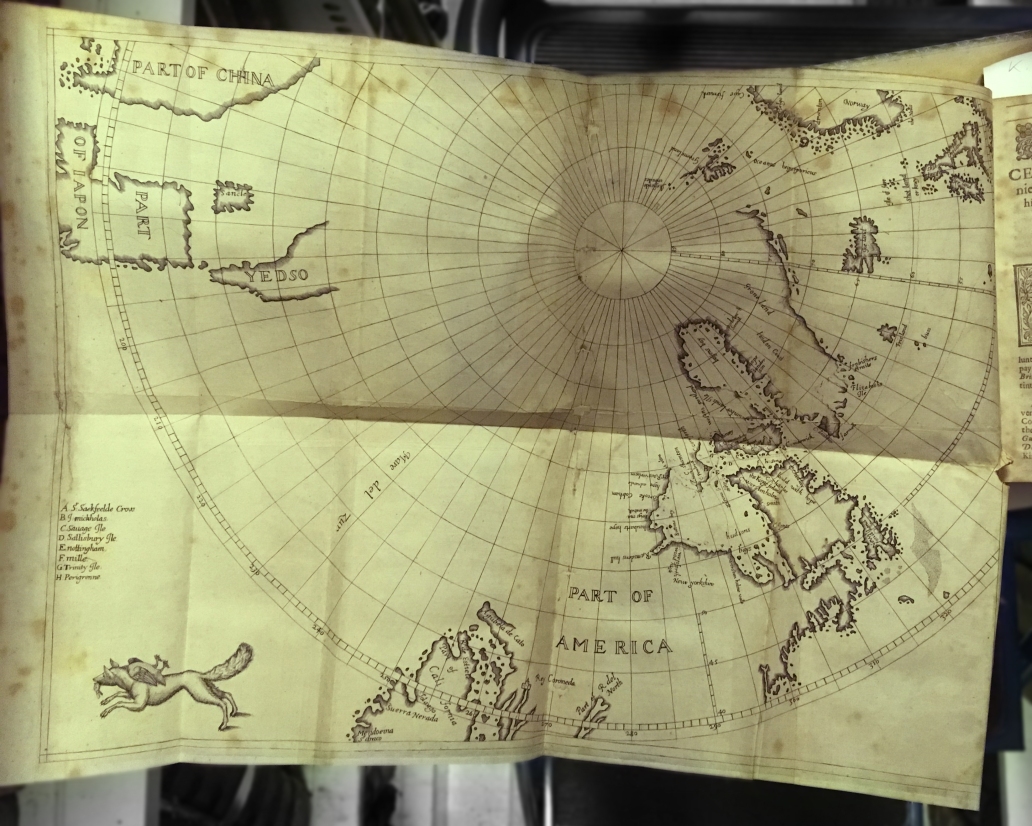

The Northwest Passage is also a major theme in theDivers voyages。游记确信能找到, and should be found by the English. In the end, the Northwest Passage was first navigated successfully in 1903–1906 by the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who was also first to reach the South Pole. Hakluyt included Michael Lok’s map of the north Atlantic in the book to further his theory, alongside a general world map. The book at the University of Glasgow is one of only four in the world to retain both maps.

Michael Lok’s map of the north Atlantic, dedicated to Sir Philip Sidney and published in Hakluyt’sDivers voyages。The British Isles and Europe are shown at the top right.

The map is extremely skewed, with the islands off the coast of Canada shown in great detail in contrast to the rest of north America, and simply fades away in the Canadian interior. This is common for early maps of America, like the one below, from another Hutton book,North-West Fox, or, Fox from the North-West Passage,Luke Fox’s 1635 account of his voyage in search of the Northwest Passage. Japan and China appear, but everything between the Hudson Bay and the Pacific is blank.

Map fromNorth-West Fox, or, Fox from the North-West Passage。Note the fox depicted in the bottom left corner.

These books are just a few from Hunter’s vast collection, every one of which has a fascinating story attached to it. Some of the books mentioned above will be on display in the Special Collections foyer from January to April 2018 as the first part of William Hunter’s Tercentenary celebrations, so be sure to take a look.

Featured University of Glasgow Library Special Collections items:

- Colmenero,Chocolate or an Indian drink(Sp Coll Hunterian Cm.2.31)bought from Hutton sale for one shilling

- Hakluyt,Divers voyages touching the discoverie of America(Sp Coll Hunterian Cp.3.16)

bought from Hutton sale for eight shillings and sixpence - Hakluyt,The principal navigations, voiages, traffiques and discoveries of the English nation(Sp Coll Hunterian K.3.1-2)

- Zárate,The history of the discovery and conquest of the provinces of Peru(Sp Coll Hunterian Cp.3.13)

bought from Hutton for nine shillings and sixpence - Gorges,America painted to the life(Sp Coll Hunterian K.7.7)

bought from Hutton sale for two shillings and sixpence - Cieza de León,Crónica del Perú(Sp Coll Hunterian K.8.11)

References and Further reading

- Biografías y Vidas。Agustín de Zárate

- Coe and Coe 2007。The true history of chocolate。London: Thames and Hudson

- Fuller 1995。Voyages in print: English travel to America, 1576–1624。Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Galeano 1973。Open Veins of Latin America。New York: NYU Press

- Jones 2015。When chocolate was medicine: Colmenero, Wadsworth, and Dufour。Public Domain Review blog

- Payne。Richard Hakluyt’sDivers Voyages: a census of the surviving copies。The Hakluyt Society

- Presilla 2001。The New Taste of Chocolate: a cultural and natural history of cacao with recipes。Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press

- Quinn 1974。The Hakluyt Handbook, volume 1。London: The Hakluyt Society

- Ward 2013.Sixteenth-century philosophical and linguistic strategies: mental colonialism, the nation, and Agustín de Zárate’s largely forgotten ‘Historia’.Latin American Literary Review41. 27–67

Find out more about William Hunter’s Library: a transcription of the early catalogues

Follow the project on Twitter at #WHL1783

Categories:亚洲博金宝188

Scrapbooking Old English with Edwin Morgan – ‘the nerves must sometimes tingle and the skin flush’.

Scrapbooking Old English with Edwin Morgan – ‘the nerves must sometimes tingle and the skin flush’. David Murray Book Collecting prize 2022: the winners!

David Murray Book Collecting prize 2022: the winners!

Reblogged this onruthfletcherhunterian。